A History of My Homelab

Valentin Haudiquet

Software Engineer

Recently, I migrated the services I host to an enterprise server (a Dell R740) running from my home. This is the latest significant step in my homelab, where I can both experiment and host production services. This is a good excuse to make a technical retrospective of how it all started and evolved into what it is today.

Getting Started: Hosting a Website

Web Hosting Service

My homelab journey began around 2016, when I was 15. Back then,

all I wanted was to host a personal website. I had no idea what a "homelab" was,

nor did I know that you could host a website from a home connection

using ordinary hardware. I ended up using Hostinger,

a web hosting service that offered a free plan at the time. It included a free

subdomain which I happily accepted. That's how valou3433.pusku.com became my very first website.

Raspberry Pi

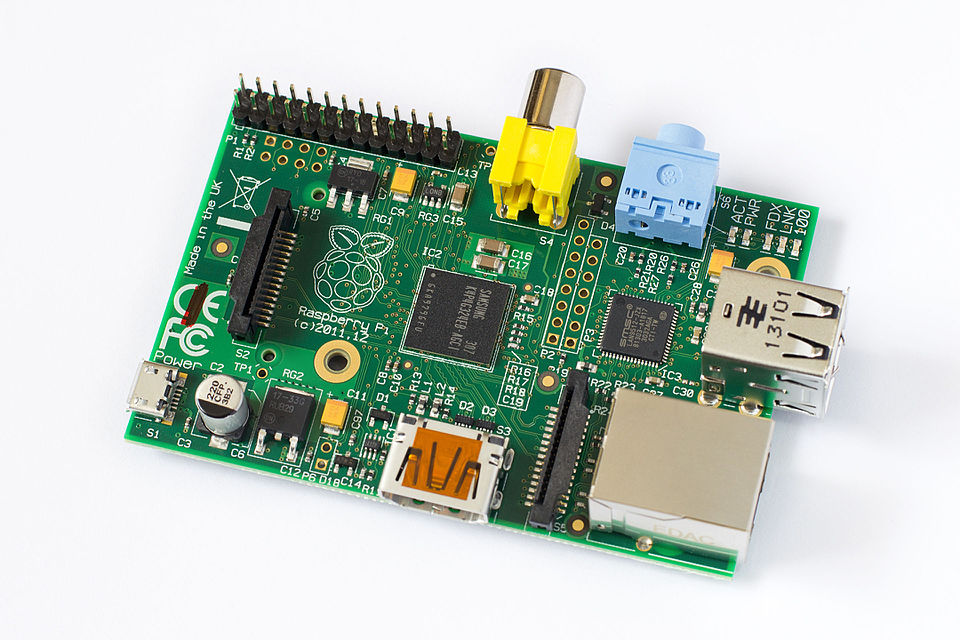

Hosting a website was mostly about proving to myself that I could do it, and partly about showing off to friends (as well as sharing simple, fun projects I had built at the time). When I received a Raspberry Pi as a gift (for my birthday or Christmas, I can't recall) and realized (thanks to previous experience with Minecraft server hosting) that I could host my website on it, I immediately started configuring it that way.

The Raspberry Pi Model B (or 1B), one of the first low-cost consumer Single Board Computers (SBC). Essentially, a board with an integrated CPU, RAM and I/O that can act as a full computer; or in my case, a mini-server. Image credits: Tors, Wikipedia, CC-BY-SA 3.0

This became my de facto first homelab, allowing me to learn how to configure a web server, and leaving me wanting more. Before long, I was also running an FTP server, which I used for file sharing between computers as well as backups. It turned out to be disastrous, as the SD cards I used with the Pi got corrupted multiple times; but it was really fun!

First Home Server

After high school, I entered a French prépa (classes préparatoires), a two-year intensive program preparing students for competitive entrance exams for engineering schools. It was mostly math and physics, which didn't leave much time for personal projects.

However, with COVID, my second year became quite unusual: France was in full lockdown just before exams, and some were canceled; so I decided to retake it. My third year was lighter and finally allowed me to spend time on personal projects again.

I also had my first apartment at that time, and quickly bought an old NAS server to share files between my computers, including laptops and machines at my mom's house.

My first NAS (Network Attached Storage) server. Basically, a box where you insert disks, connect a network cable, and it makes the files available over the network. Image credits: InfoDepotWiki

The NAS was a D-Link DNS-323, released in 2006, featuring a 500MHz ARM CPU and 64 MiB of RAM. It ran a proprietary operating system, and after hacking it to install a stripped-down Linux distribution, it became somewhat unusable. The file sharing was outdated and slow, and I didn't have enough RAM to even hope installing applications. I clearly needed something more powerful.

Soon after, I built my first real home server:

- Fractal Node 304 case

- 350 W SFX power supply

- 4 TB WD Red Plus HDD

- Smaller SSD for the system

- 8 GiB SO-DIMM DDR4 RAM

- ASRock J4105-ITX motherboard with a soldered low-power 4-core Intel Celeron J4105 CPU

Unboxing all the parts before assembly

At the time, I was using Arch Linux on my laptop and decided that it would be a good idea to use it on the server too. I set it up, and natively installed software: a web server, Jellyfin, Transmission torrent client, and Nextcloud.

Deploying applications natively turned out to be a management nightmare. The deploying part was not that bad, but it needed extra steps like installing and configuring dependencies, and editing configuration files directly. Once everything was set up, through Arch Linux packages or AUR packages, keeping the server up to date was the difficult part. I remember a specific issue I had where Jellyfin needed an older version of the .NET runtime, but another app needed a newer one, and they were both conflicting. This was not the only issue, and overall, deploying applications natively does not seem like a good idea in modern times for a setup that isn't 'basic' like a simple web stack.

The server stayed in my apartment and worked well for a year. During summer, I moved back to my mom's house, then to Rennes for studies in a studio apartment, leaving the server behind.

First Real Homelab

Main Server: Lenovo P330

Fast-forward a year, I met my girlfriend in Rennes, and we decided to move in together. This allowed for a larger apartment, with enough room for a new server. I ended up buying a Lenovo P330 Tower SFF.

Technical specifications:

- Intel Xeon E-2134 CPU @ 3.5 GHz

- 64 GiB DDR4 ECC RAM (max)

- 1 TiB NVMe SSD

- NVIDIA Quadro P620 GPU

- Intel X520-DA2 SFP+ 10 Gbps NIC

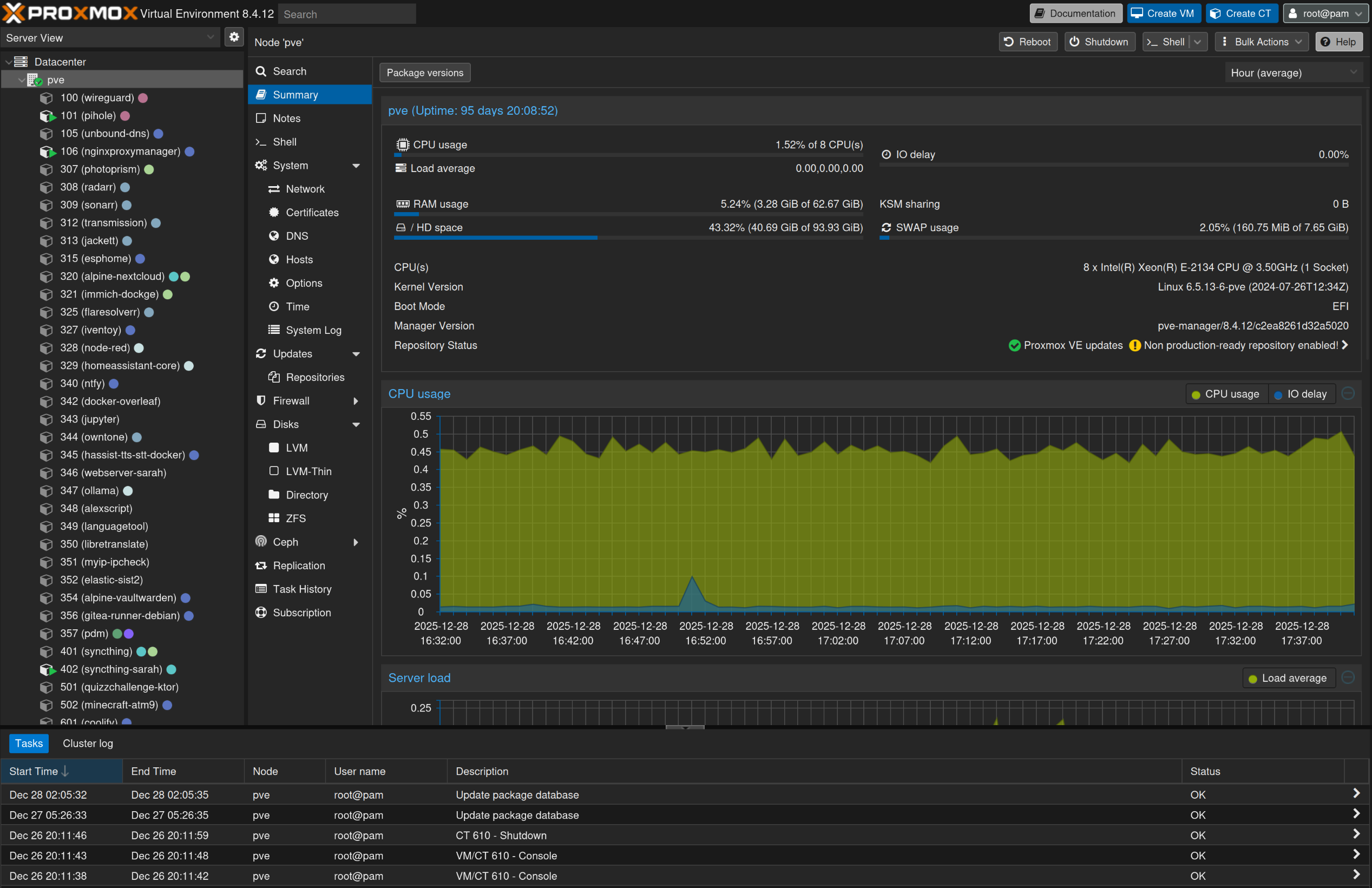

Having done more research this time, I wanted to try Proxmox. I installed it on that server, and started with LXC containers; first manually, then with community-scripts.

Proxmox VE is an operating system based on Linux Debian, that provides a web interface allowing to manage QEMU-KVM hardware-accelerated virtual machines (VMs) and LinuX Containers (LXC). LXC is a technology using Linux kernel features (CGroups, kernel namespaces, chroots) to provide 'system containers', isolated but sharing the same kernel. Like a virtual machine, but with less isolation and less overhead.

I started using software like Pi-Hole (ad-blocking DNS server), reverse proxies, and more advanced services like the *arr stack, Photoprism, Gitea, Home Assistant, NodeRed, Syncthing and others.

NAS Server

Given the 'SFF' nature of that first server, hard drive support was quite limited. I wanted to level-up my local storage capacity, so I decided to build a NAS server that would look more professional. I made a few mistakes on the way, but it was a good experience overall. I documented the build process in a YouTube video, which, unfortunately for my English-speaking readers, is in French.

I use the TrueNAS operating system (Debian-based) for my NAS. I set up multiple ZFS pools, with a mirror of two 4 TB hard drives for my personal data, a 12 TB hard drive for disposable data and a mirror of two 128 GB SSDs for fast application data. I also set up off-site backups to my old server, still at my mom's house, using ZFS replication.

This also meant that I now had two servers, and needed to set up fast networking between them. I bought and learned to use 10Gbit SFP+ cards, fiber optic cables and modules.

Networking

To connect the servers and my computers, I bought a QNAP QSW-M408-4C managed switch. It had 4 SFP+/RJ45 combo 1/2.5/5/10 Gbps ports, and 8 RJ45 1 Gbps ports. It is a wonderful switch, but was a bit noisy, so I replaced the stock fan with a Noctua. It still serves me well, and given the many possible speeds, it is a useful switch.

The QNAP QSW-M408-4C (image credits: QNAP)

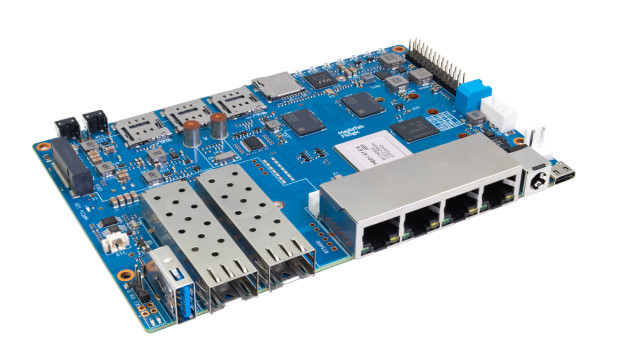

I also wanted to advertise my DNS server over DHCP, and wanted to get rid of my ISP-provided router. I bought a Banana PI BPI-R4, which I use as router with OpenWRT to this day. It is quite useful: advertises Pi-Hole as DNS server automatically, can manage different VLANs (virtual sub-networks) for regular use, servers, guests, and IoT devices; and can act as a Wireguard VPN peer.

The BananaPi BPI-R4. Don't worry, I have it in an enclosure :)

That last part is interesting for two reasons. First, I sometimes want to access home services while away. The easiest solution would be to expose the service to the internet, which I sometimes do for public-facing projects (for example: this website). However, this means that if there is a security issue with the app, anyone could take advantage of it. For most services (like my personal photo gallery Photoprism), I don't want to have them publicly accessible. There are many known solutions for this (Cloudflare Tunnels for example), but my personal take is just to connect to my local network with a VPN. This way, I can access the services but also the servers directly, as if I was always at home. It has downsides (if you want to share this to other users, they need to know how to configure a VPN), but it works for me. Some solutions (like Tailscale) allow to have a nice UI and client to manage the VPN settings and credentials, but I'm fine with editing Wireguard configurations by hand (or using OpenWRT Wireguard integration).

Another use of Wireguard is site-to-site VPN. My old server, still at my mom's house, is useful for off-site backups. It is directly reachable from my network as the router will route packets through Wireguard automatically, without any configuration needed on the client. My local IP range is something like '10.1.0.0/16', and the second site, my mom's house, has IP addresses under '10.2.0.0/16'. The OpenWRT routers on both sides have special rules to route those IPs through Wireguard.

There are a ton of interesting things around networking, but I'm still very much a beginner in the matter. As long as that part worked for connecting my two servers, I was able to move on and use them to deploy more services.

Docker

For a while, I was happy with that setup; but after a bit of time I stumbled upon an application that was only distributed as an OCI image. I did not know much about Docker at the time, but I quickly had to learn about it.

Docker is a software solution allowing for application containers.

Unlike LXC/system containers, an application container typically only ships what is needed to run a specific application.

For example, it would not contain systemd, nor system tools, but only the libraries needed to run the app. This allows

for easy deployment (and distribution) of applications, as easy as docker run app:latest (if the developer ships an OCI

image for the app).

The Open Container Initiative (OCI) defines container runtime, image format, and distribution. Docker can run and pull OCI images, in an OCI-compliant way.

At first, it felt awkward. I had one LXC container running a Docker instance for each Dockerized app.

It felt off to SSH into those machines to copy docker-compose.yml files and start containers with

docker compose up.

However, after a while, mostly after seeing this video, it started to click. I started managing my repo of compose files, had one large virtualized Docker instance, and could deploy directly from my laptop using Docker contexts.

Like in the video, I also learned to use Docker Swarm and Gitea actions to deploy my own Nuxt.js application, BuildPath.

I loved the idea of automatic deployment, checked out in git, automatically managed by a controller.

Kubernetes: k3s and Talos

Learning about this kind of deployment naturally led me to hear about GitOps practices, that are mostly adopted for Kubernetes deployments. So I had to learn Kubernetes.

Kubernetes is an open-source system for automating deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications (from kubernetes.io). Essentially, it is a container orchestrator, not only running containers like Docker but also scheduling them on multiple nodes, managing their lifetime, external connections with load balancing, and many more.

I started by deploying a VM with k3s, since it was presented to me as "the Kubernetes distribution that is the easiest to use". I quickly deployed example services, using manifests, but nothing felt "GitOps", only declarative, and only for the services.

This is when I discovered Talos Linux and FluxCD (as well as ArgoCD).

Talos Linux is a minimalist, immutable Linux distribution designed for Kubernetes. Everything, including the OS, is managed declaratively; and the only programs bundled or installable are the Kubernetes executables and libraries.

FluxCD is a tool keeping a cluster in sync with a Git repository (or other sources). It deploys or deletes services automatically, after each commit/push, applying the declared configuration checked out in Git.

Talos allowed me to have everything, including the OS, managed in a declarative way. Flux allowed the services to be deployed and synced automatically from a git repository. It was everything I wanted, so I started to use it. That was the start of my homeprod repository.

Kubernetes also has formidable features and tooling, allowing for a much better quality-of-life than docker. For example, with Docker, when deploying a new service 'appxyz', and adding the Traefik (reverse-proxy) annotation 'host=appxyz.lan', I still have to go to my local DNS server (Pi-Hole) and add a binding for 'appxyz.lan'. On Kubernetes, with ExternalDNS, creating the ingress will directly create the DNS mapping in Pi-Hole. Nice!

There are a lot more interesting features: from a consumer perspective, Helm charts are wonderful (even though they seem hard to write). The only part left to configure is the app configuration, unlike with docker-compose where you have to manually specify which database container you want to run, which Redis, ... The only downside is that the Helm chart setup is more verbose.

I still have a lot to learn about Kubernetes, and consider myself far from an experienced user.

The Missing Piece: IaC

I still had one issue: I was deploying the Talos VM by hand on my Proxmox host. This felt inconsistent, knowing that everything else was managed in the repo by controllers. This is when I discovered Infrastructure as Code (IaC).

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is managing infrastructure (virtual machines, for example) declaratively, as code files, instead of in a procedural way (using commands or interfaces to deploy). For example, instead of interacting with a cloud dashboard to request and configure a new VM, you would modify a file adding a VM definition and configuration and then call a controller to reconcile the real infrastructure.

Terraform is such a controller and language, that supports providers like AWS, Azure or even Proxmox.

I quickly wrote my first Terraform files, that would deploy and kickstart my Talos VM, as well as a few others.

resource "proxmox_virtual_environment_vm" "kube" {

name = "kube-${var.proxmox_node_name}"

description = "Kubernetes Talos Linux"

tags = ["kubernetes", "talos", "terraform"]

vm_id = 702

cpu {

cores = 20

sockets = 1

type = "host"

}

memory {

dedicated = 32768

floating = 16192

}

cdrom {

file_id = proxmox_virtual_environment_download_file.talos-cloudimg.id

interface = "ide0"

}

disk {

...

}

...

}

Extract of the Terraform code file used to deploy the Talos Linux VM on Proxmox

Enterprise Servers and a Rack

In the meantime, I had done the terrible mistake of installing the eBay app on my phone. I discovered listings for used enterprise rack servers, and immediately bought one as a test, but quickly discovered that the noise made it unusable in an apartment.

Fortunately, my girlfriend and I later moved from Rennes to Toulouse, and found a small house, with a small garden that had an independent room. That was all the justification I needed to start looking for a rack. I found one on Leboncoin, a French website for used goods, for cheap.

Installing the empty rack in the now server room. It came with a good UPS, which I still use today. As you can see, I'm behind it trying to wire everything up.

The rack, populated with previous rack servers as well as the P330 and the NAS.

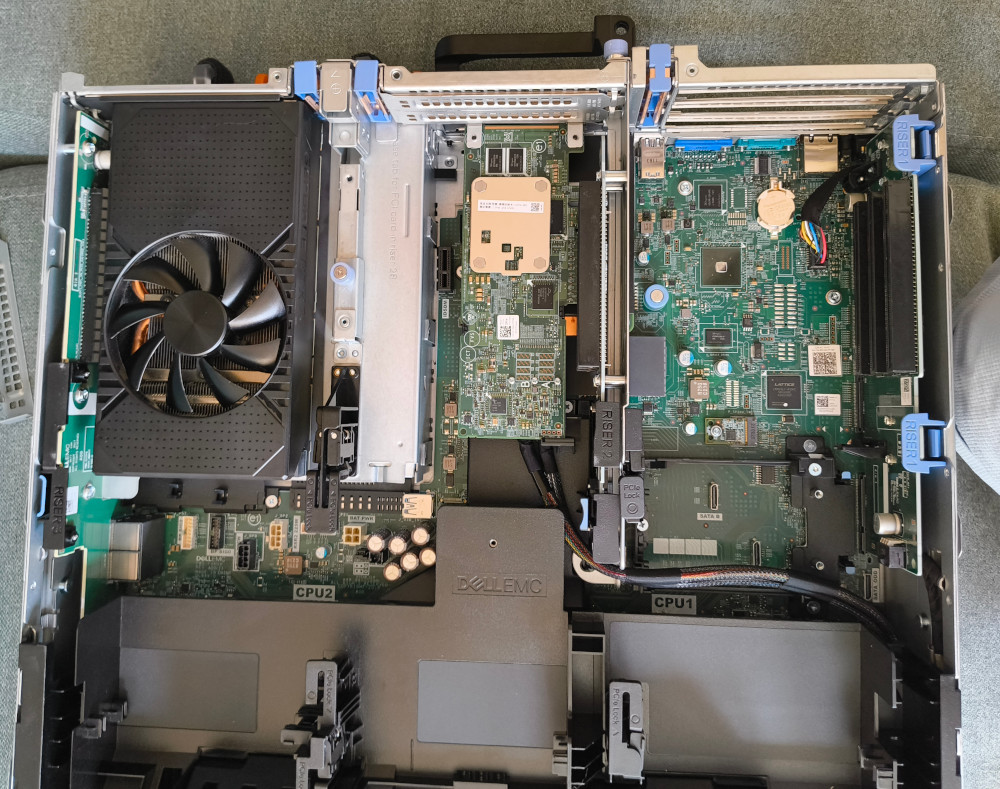

After a while, I also bought the server I'm using today: a Dell PowerEdge R740.

This server has impressive specifications:

- 2× Intel Xeon Gold 6138 CPUs (20 cores / 40 threads each)

- Up to 3 TB DDR4 ECC RAM (24 DIMM slots)

- 12× 2.5" drive bays

- Quad 10 Gbps RJ45 NIC

I'm currently finishing the migration of every service from my old P330 to the R740. I'm also migrating the NAS, as I now have a rack-mounted disk enclosure with an HBA card.

The Dell PowerEdge R740 (2U server)

The 3D-printed disk enclosure I use with the R740 for my virtual NAS (still missing a few pieces on the picture).

The R740 is powerful enough to act as a build environment, using ephemeral VMs, which is very useful for my work at Canonical. It also includes iDRAC (Integrated Dell Remote Access Controller), Dell's implementation of IPMI for remote management.

IPMI (Intelligent Platform Management Interface) is a specification for independent management of a system. For example, with IPMI, you can shutdown but also power on a system, set virtual cd-rom drives from ISO images for operating system installation, send remote mouse or keyboard events and watch video output of the server. Usually, a KVM (Keyboard Video Mouse) can have the same functionality when plugged in consumer hardware, like the PiKVM, NanoKVM or others.

What About Docker?

My Kubernetes setup migrated seamlessly to the new server: I just updated some Terraform variables, redeployed Talos (applying the new Terraform configuration), and Flux pulled everything automatically. But my Docker setup still required manual redeploys from compose files, which felt out of place.

Fortunately, a similar GitOps workflow is theoretically possible for Docker, even if it supports a lot less features than Kubernetes out of the box. SwarmCD is a project aiming at giving the same kind of experience for Docker Swarm that FluxCD or ArgoCD are giving for Kubernetes (i.e. a GitOps workflow, basically). I'm currently using an experimental branch of that project, and even contributed to add support for some of my specific workflows. It is still far from something like FluxCD, but provides really interesting functionality. Just like with Talos, I can use Terraform to deploy and kickstart SwarmCD.

Local AI experiments

Another thing that motivated me to move to a more powerful server is the ability to run local AI models. I had three use cases in mind:

- Running local LLM models, connected to tools like Home Assistant for home control (maybe with a speech-to-text model as entry point)

- Running code-specialized models, to test autocomplete features as well as development with local agents (using llama-vscode and Cline)

- Running image generation models, using ComfyUI. Some of my friends were playing with online image generation and sharing results, and I wanted to see if local models could achieve the same.

I bought a used RTX 3060 12 GB for cheap (on Leboncoin as well), but of course it didn't fit in my SFF server. I used another computer for a while, and only powered it on for experiments. I feel like I'm ready to have some of it more permanent (for example, a tiny model connected to Home Assistant), and the R740 had space for that GPU, which is great. I can also add a lot of system RAM, which is unfortunately necessary for most interesting models.

The RTX 3060 12GB installed inside the R740 server (top left). I had to buy a specific power cable that goes from the motherboard to the GPU (not shown here).

Wrapping Up

It has been a wonderful journey!

From a simple Raspberry Pi with defaults SSH/web/FTP servers, I went to a real home server where I could natively deploy applications. It then evolved into a Proxmox server, where I learned about virtualization and system containers. I also learned about Docker, and then Kubernetes, GitOps, and IaC.

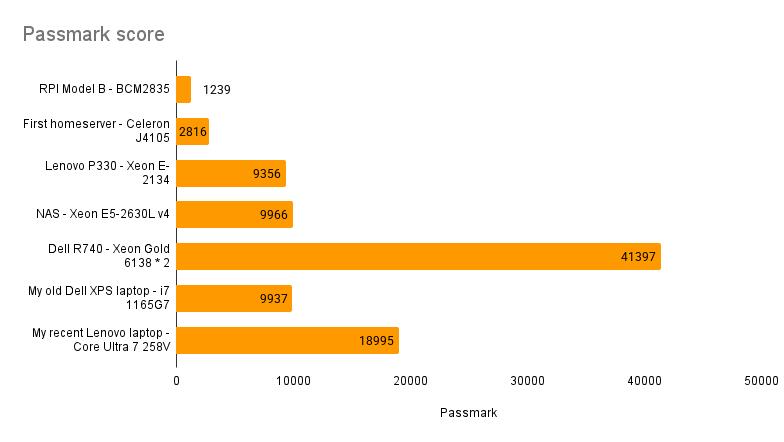

Passmark benchmark score for different servers of my Homelab, as well as my laptops for comparison

I'm now using a full-blown rack server, but I'm not sure I'll stop there. Some people are becoming their own internet service provider / autonomous system, doing crazy home automation, or even have a multi-site homelab.

I would really like to try all of that, but I'm currently finishing migration to the new server and learning about IPv6 and related technologies (NAT64, ...). My issue with IPv6 right now is that my ISP does give me a prefix, but I cannot delegate it to my router (the ISP-provided box does not support prefix delegation); which is something I will need to work around.

I still have a lot to learn and a lot to do to make my homelab clean.

You can follow/check out everything on my homeprod repository!